As the ketogenic diet gains popularity, it’s important to have a balanced discussion regarding the merits of this diet. Let me emphasize right out of the gate that this is not a diet without merits (excuse the double negative); in fact, it has significant therapeutic potential for some clinical pathologies. However, it is also a diet with inherent risk, as evidenced by the extensive list of adverse reactions reported in the scientific literature—and this has not yet been a thorough enough part of the public discussion on ketogenic diets.

This is the first of a series of articles discussing various facets of a ketogenic diet with an inclination toward balancing the discussion of the pros and cons of this high-fat, low-carb, low/moderate-protein diet. My interest in this topic stems from concerns I have over its general applicability and safety, simultaneous with its growing popularity. I feel a moral and social obligation to share what I understand of these diets, from my perspective as a medical researcher. The dangers of a ketogenic diet was, in fact, the topic of my keynote presentation at Paleo F(x) this year (links to video will be provided once available). This series of articles will share the extensive research that I did in preparation for this presentation, including all of the topics covered during my talk as well as several topics that I didn’t have time to discuss (also see the free PDF Literature Review at the bottom of this post).

For every anecdotal story of someone who has regained their health with a ketogenic diet, there’s a counterpoint story of someone who derailed their health with an identical diet. I’m not here to trade anecdotes. I’m here to cite a collection of scientific papers, including results from clinical trials, case studies, and mechanistic studies that show a potential dark side to the ketogenic diet. And that dark side is one that everyone needs to be aware of while they perform their own individual cost-benefit analysis to decide whether this dietary strategy is worth attempting for them.

Where Do Ketogenic Diets Come From?

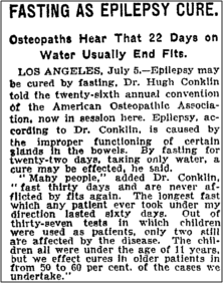

The origins of the ketogenic diet were the observations of Hippocrates in 500BC that fasting could reduce and even cure epileptic seizures (fasting is also a ketogenic state, more on that in a future post). However, it wasn’t until 1911 that the first scientific study on starvation as epilepsy treatment was published. Two French doctors, Guelpa and Marie, observed that a 4-day fast decreased seizure frequency in 20 epileptic children and adults, which led to “La cure du Dr. Guelpa”, a prescribed treatment for epilepsy that consisted of fasting followed by a very limited vegetarian diet. Dr. Hugh Conklin popularized fasting (three days to three weeks) as a way to cure numerous illnesses, including epilepsy. The banner was taken up in 1921 by endocrinologist Dr. H. Rawle Geyelin, who was the first to document cognitive improvement resulting from fasting in a scientific study performed on 26 epileptic patients.

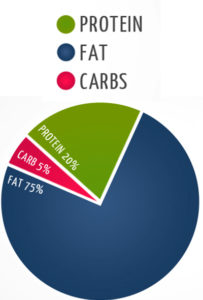

Fasting has one very important barrier to rampant clinical use: it’s not sustainable. You can’t starve for the rest of your life and expect it to last very long. In 1921, Drs. Stanley Cobb and W.G. Lennox became the first to observe that control of seizures by fasting occurs via a change in body metabolism that can be induced either by absence of food or by a very low carbohydrate intake. And this observation led to the birth of a form of nutritional starvation, the ketogenic diet, a term coined by Dr. Russell Wilder who developed the diet as an alternative to fasting and demonstrated its comparable effectiveness in epilepsy. Dr. Wilder observed that the diet produced high levels of ketone bodies in the blood and hypothesized that a high fat, low carbohydrate diet would mimic the anticonvulsant effects of fasting because limited glucose supply would force fat to be metabolized into ketones, which could then be used as an alternative fuel by the brain (this hypothesis took decades to prove, and the more detailed mechanisms remain largely a mystery). In 1925, Dr. Mynie Peterman, calculated the exact formula for nutritional ketosis, a daily diet comprised of: 10 – 15 grams of carbohydrate, 1 gram per kilogram of bodyweight of protein, and the rest fat (a macronutrient formula that is still within the narrow range used in various ketogenic diet variations today) . In the earliest epilepsy studies, calories were restricted to 75% of daily allowance, although the need for calorie-restriction concurrent with ketogenic diets for the treatment of epilepsy has since been disproved.

Research into ketogenic diets went through many ups and downs over the decades that followed. Every time a new anticonvulsant drug for epilepsy was developed, interest in ketogenic diets waned under the presumption that it’s easier, and more tolerable, to take a pill every day compared to a severely restrictive diet. However, interest was rekindled in the wake of professional and public recognition subsequent to: the popularity of the Atkins’ Diet Revolution; a Dateline report featuring a 2-year-old Charlie Abrahams whose intractable seizures are successfully stopped after he adopted a ketogenic diet; the creation of The Charlie Foundation which disseminates informational ketogenic diet videos to doctors and dieticians; and the movie Do No Harm. Since the late-1990s, research into ketogenic diets has expanded, including a series of long-term ketogenic diet studies for refractory epilepsy (epilepsy that did not respond to anticonvulsant drugs) and investigation of a variety of other applications such as weight loss, tumor shrinkage, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

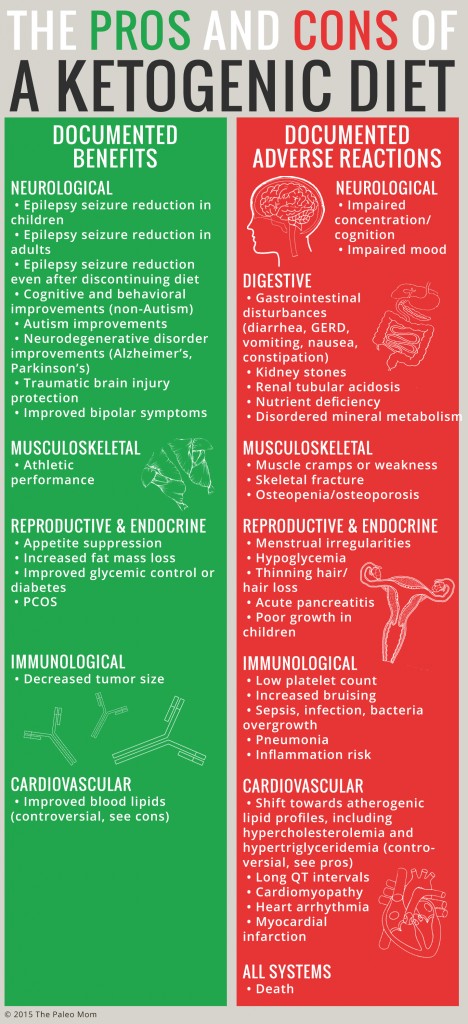

Adverse Reactions to Ketogenic Diets

As the list of health conditions that may be at least partially alleviated by ketogenic diets increase (and which currently includes epilepsy, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Autism, traumatic brain injury, bipolar disease, PCOS, cancer, obesity, and diabetes), so too does a body of literature pointing to common side effects and potential adverse reactions.

Adverse reactions to a ketogenic diet have been reported in the scientific literature. Yes, even including well-designed clinical trials performed and published very recently. In fact, the intolerability of side effects and adverse reactions is the primary reason for trial participants to drop out of clinical trials (other reasons for trial drop-outs include ineffectiveness of the diet, and that the diet is too hard to follow).

Adverse reactions are not the same thing as side effects. An adverse reaction is an, unwanted/unexpected and dangerous reaction to a therapeutic agent. In contrast, a side effect is a secondary, typically undesirable effect of a therapeutic agent. More simplistically, side effects are minor and adverse reactions are not. Side effects are typically what are reported in shorter-term studies, where as both side effects and adverse reactions are reported in the long-term ketogenic dietstudies (typically 6 months to 2 years, but any study that allows for keto-adaptation, which takes up to a month, can be considered long-term). This article is not a discussion regarding side effects, the list of which has some overlap with the list of adverse reactions (for example common side effects include minor gastrointestinal symptoms). This article is to draw attention to the documented adverse reactions, which include:

- Gastrointestinal disturbances (diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, constipation, GER)

- Inflammation risk

- Thinning hair/hair loss

- Kidney stones

- Muscle cramps or weakness

- Hypoglycemia

- Low platelet count

- Impaired concentration/cognition

- Impaired mood

- Renal tubular acidosis

- Nutrient deficiency

- Disordered mineral metabolism

- Poor growth in children

- Skeletal fracture

- Osteopenia/osteoporosis

- Increased bruising

- Sepsis, infection, bacteria overgrowth

- Pneumonia

- Acute pancreatitis

- Long QT intervals

- Cardiomyopathy

- Shift towards atherogenic lipid profiles (including hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia)

- Heart arrhythmia

- Myocardial infarction,

- Menstrual irregularities and amenorrhea

- Death

That’s a long list. A long list of not-good things. And did you can’t that last one? Five scientific papers have reported deaths as an adverse effect from long-term ketogenic diets (here’s the citations: Stewart, et al., 2001, Kang, et al., 2004, Kang, et al., 2005, Bank, et al., 2008, Suo, et al., 2013 and make sure to check out the free PDF download of my Literature Review at the bottom of this post which contains details on all of the papers reporting adverse reactions). Two of these papers are case studies, and the other three are papers derived from two separate clinical trials, all studies in epileptic children. Some of the deaths can be attributed to extra complications from secondary conditions or accidents that befell the child during the course of the clinical trial; however, other deaths—most typically from severe infection or heart disease—are attributed directly to long-term ketosis.

The Relevance of Adverse Reactions

I believe the potential for adverse reactions is important information for people to know when they are weighing a ketogenic diet versus other diets or therapeutic options. But, that doesn’t mean that everyone need avoid ketogenic diets. It’s a question of weighing the pros and cons for each individual. And certainly some of the above adverse reactions can be prevented with careful choice of foods and/or targeted supplementation (such as nutrient deficiency). And it’s important to emphasize that the above list of adverse events also points to a long list of tests that can be performed regularly by a supervising health professional to monitor for any potential detriment in the event that there are compelling reasons to undertake a ketogenic diet.

When you read reports expounding on the benefits of a ketogenic diet, purporting that there is no risk involved or at least no risk for most of us, the origin of this dogma is either a selective reading of the science (which may be unintentional—I’m not a conspiracy theorist) or a bias-motivated dismissal of any scientific studies to the contrary of this narrative. For example, I’ve heard these adverse reactions described as “minor” and “transient” or attributable in some way to “people doing keto wrong”, statements that are not actually substantiated by the scientific literature (although, those might be fair appraisals of side effects from short-term studies). As a second example, I’ve heard declarations that the long-term ketogenic diet studies in children with refractory epilepsy are irrelevant since these children are not robust, heathy kids and many of them (although certainly not all) are simultaneously taking anticonvulsant drugs while following a ketogenic diet to mitigate severe, frequent seizures. Because the overwhelming majority of the long-term ketogenic diet studies have thus far been performed in the context of epilepsy, this is the field of research that has most thoroughly reported adverse reactions. Certainly, these kids belong to a more sensitive population (why documented deaths as a result of adverse reactions to a ketogenic diet have occurred almost exclusively in epileptic children), but that doesn’t mean that these reports don’t provide extremely useful information, or a warning worth heeding (another double negative!). After all, it’s not typically the robust healthy person who experiments with ketogenic diets to improve their health—and while death is probably very unlikely, the potential harm to other body systems (cardiovascular, immune, endocrine, digestive) remains.

When you read reports expounding on the benefits of a ketogenic diet, purporting that there is no risk involved or at least no risk for most of us, the origin of this dogma is either a selective reading of the science (which may be unintentional—I’m not a conspiracy theorist) or a bias-motivated dismissal of any scientific studies to the contrary of this narrative. For example, I’ve heard these adverse reactions described as “minor” and “transient” or attributable in some way to “people doing keto wrong”, statements that are not actually substantiated by the scientific literature (although, those might be fair appraisals of side effects from short-term studies). As a second example, I’ve heard declarations that the long-term ketogenic diet studies in children with refractory epilepsy are irrelevant since these children are not robust, heathy kids and many of them (although certainly not all) are simultaneously taking anticonvulsant drugs while following a ketogenic diet to mitigate severe, frequent seizures. Because the overwhelming majority of the long-term ketogenic diet studies have thus far been performed in the context of epilepsy, this is the field of research that has most thoroughly reported adverse reactions. Certainly, these kids belong to a more sensitive population (why documented deaths as a result of adverse reactions to a ketogenic diet have occurred almost exclusively in epileptic children), but that doesn’t mean that these reports don’t provide extremely useful information, or a warning worth heeding (another double negative!). After all, it’s not typically the robust healthy person who experiments with ketogenic diets to improve their health—and while death is probably very unlikely, the potential harm to other body systems (cardiovascular, immune, endocrine, digestive) remains.

The Need For More Science

The body of scientific literature on ketogenic diets is surprisingly sparse when you consider the therapeutic applications of this diet have been in effect for nearly a century. A mere 1592 scientific papers are returned by PubMed (the US National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health online medical research database) with the search term “ketogenic diet”. It’s not that other diets are more thoroughly researched per se, but certainly other therapeutic strategies to mitigate disease, the most relevant example being anticonvulsant drugs for epilepsy (c.f. PubMed returns 135282 scientific papers with the search term “anticonvulsant drugs”) are monumentally better understood before being approved for use.

Frankly, research is just beginning to scratch the surface in terms of understanding how ketogenic diets work to reduce seizures in epilepsy or to provide the other documented benefits. Why is that important? Because the extensive list of documented side effects and adverse reactions indicate that the positive health effects of a ketogenic diet comes at a cost, one that may not be acceptable to many. Understanding how a ketogenic diet works to provide a benefit, also gives clues as to why it causes adverse reactions. And because the documented adverse reactions include serious illness and death, understanding why these might come about is a prerequisite for adopting this therapeutic strategy in a more widespread way. What insight we can glean from mechanistic studies will be the topic of several future articles.

Does the need for more science give ketogenic diets a green light or a red light? I certainly agree with the ketogenic diet community that more long-term and mechanistic studies are required. However, I disagree that, in the absence of the insight this research could provide, that everyone should just “try it for themselves”. We need to look at the information currently available for guidance. The studies do not ubiquitously show benefits; not everyone responds positively to a ketogenic diet; many unanswered questions regarding the effects (both positive and negative) of ketogenic diets remain; serious adverse reactions have occurred. As a community, we have a choice: proceed with great abandon, or have a more nuanced and accurate conversation of what we know versus what we don’t know. I support the latter and believe the capacity for harm needs to be just as much a part of the conversation as the therapeutic potential.

The Fine Print

Other diets do not trigger the same biochemical pathways that are activated by a ketogenic state. And while certainly other diets (Paleo, or the autoimmune protocol being good examples) stake therapeutic claims, the mechanisms of action are purely through micronutrient saturation and avoidance of foods known to be inflammatory. The ketogenic diet is different in that it was designed to emulate starvation, taking advantage of the biochemical benefits of starvation for certain body systems (mainly neurological, but this is also why weight loss is a common result of a ketogenic diet) while tolerating the detriments to other body systems (such as endocrine and immune systems). (These are even different mechanisms that a standard low-carb diet.) In this regard, the ketogenic diet more closely resembles a drug than a diet (in fact, many of the same pathways activated by a ketogenic diet are manipulated by anticonvulsant drugs), which should not be a deterrent in itself, but rather a caution to read the fine print and talk to your doctor before embarking on this course—especially if going “off-label” and using a ketogenic diet for purposes that have not yet been well studied. And this is why a thorough understanding of both the pros and cons of a ketogenic diet are necessary in order for every individual to make the best decision for themselves.

Citations and Additional Reading

Normally, my science-based posts contain a dozen or so references at the bottom. This post is special. With the help of the sagacious Denise Minger, author of Death by Food Pyramid, I have compiled an review of the literature, with a particular focus on the studies that report on and potentially explain the mechanisms behind adverse reactions (there are plenty of reviews available on the internet reporting the documented benefits). This review also includes links to original publications and summaries of over 80 scientific papers that I read in preparation for writing this blog post, the future posts that I’m working on in this series, as well as my Paleo F(x) 2015 talk. Download this free PDFhere.

Article Source : http://www.thepaleomom.com/2015/05/adverse-reactions-to-ketogenic-diets-caution-advised.html